Once again I will take a moment to dig into the interesting interaction between the Emergent conversation, and Pentecostal/Charismatic Christianity.

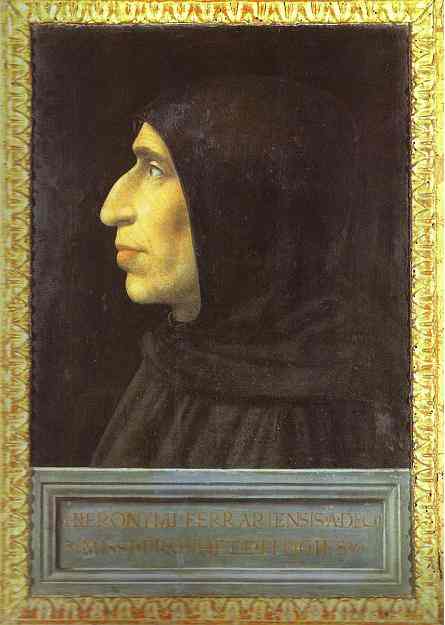

Mysticism is a serious pursuit among many Emergent thinkers. Ancient practices such as lectio divina, and the ritual worship art of icons are gaining popularity among Emergent Evangelicals whose traditions would at one time have avoided such interests, if not have rejected them altogether. This particular element of mysticism, and its resurgence among Evangelical Emergent thinkers is a piece of the puzzle in the Pentecostal/Emergent interaction which has a strangely twisted plot to it.

Today's Evangelicals, and more specifically Pentecostals have a kinship to the Anabaptists of old with their concern over the issue of icons. In respect for the 2nd commandment, using images as a means of creating a touch point for worship is viewed as idolatrous by many people from Pentecostal traditions. Yet, the Emergent conversation has been asking us to consider ancient mysticism. Along with the emergence of a response to postmodern culture and thought comes this renewal of medieval Christian mysticism, and with it a new appreciation for the purpose of the art of icons with their intellectual, and emotional attachment to prayer and worship.

Orthodox theology allows for an "eikon" as a representation of deity, which becomes a point of reference for access to the graces of heaven. As the Mass is more than a mere representation of the blood and body of the Lord in Orthodox and Catholic traditions, so the icon is more than a representation. It becomes an entrance into the presence of Heaven for prayer, and worship. Thus the Orthodox believer may not worship an icon, but does not struggle with the "veneration" of the icon, even to the point of kissing it.

Contrarily, Pentecostal and Evangelical churches are unadorned, and simple. No icons except that of the cross (usually empty and without the body of Christ) fill the spaces of worship. The place of worship is often deemphasized as a holy location, and the true "eikon" is believed to be the followers themselves who are God's image giving us a deeper glimpse into the redemptive story, and the character of God. Like the medieval Anabaptists, Pentecostal tradition has simplified worship to a direct relationship with no need for mediatorial help apart from that of Christ Himself. Placing anything between the believer and Jesus is viewed as a hindrance, and potentially a false "eikon" or an idol.

Consequently the Emergent conversation's movement toward medieval mysticism through such elements as icons may easily be seen by many Pentecostals as a step toward idolatry. I believe the Emergent conversation correctly asks us to consider evaluating iconography in the Orthodox traditions in a new light. It is not acceptable to judge the prayerfulness of those who utilize icons without considering the actions of the inner life - the thought process, and the theology placed behind the use of icons. It is possible for one person to utilize an icon as a teaching tool, and a reminder of the purposes of Heaven illustrated by the art of icons; and another person might actually venerate an icon to the point of idolatry.

Due to humanity's movement toward idolatry, the early Anabaptists who were drawn to simplicity must be honored for their insistence upon purging their lives from idolatrous activities. Their desire to purge the church of idolatry remains a core value of many Christian traditions. Though the idols change from generation to generation, the necessity for iconoclasts who challenge our idolatries does not.

It is in this clash of systems, the Orthodox worshiper, and the iconoclast, that we find the Emergent/Pentecostal dialogue walking the tightrope of Christian faith.

Yet the challenge of tightrope walking is as difficult for the Emergent thinker who challenges Pentecostal Emergents, as it is for the challenged Pentecostal. The day in which we live Pentecostal traditions have become the laughingstock of the religious world. Our TV preachers are the most ostentatious. Because of the early growth of the movement among the poor and uneducated, leadership has been high on passion and low in learning - much like the early days of Christianity itself. Yet the insistence upon developing an unmediated personal relationship with God marked by passion, and bypassing the human intellect is a story of mysticism which has traveled down the halls of our faith. Quakers, Pentecostals, Baptists, and Congregationalists sit in relatively unadorned churches in celebration of this. Quakers, Pentecostals, and Charismatics wait for the Spirit of the Lord to speak into their hearts and minds, often unmediated by physical items, or persons of position. Despite the over played emotionalism of TV Pentecost, the value of pursuing the ancient mysticism of traditions similar to Anabaptism - some of which reach back into the earliest days of Christianity, and into the record of the Book of Acts itself is as needful to be embraced as is the beauty of the iconography of Orthodoxy.

There are Emergent Pentecostals embracing, or at the least gaining appreciation for the ancient arts of iconography, but I am not sure that an appreciation for the unmediated radical pursuit of the ecstatic which has marked Quaker, Anabaptist, and Pentecostal traditions is receiving equal respect. The ancient practice of waiting on Pentecost for the unmediated movement of the Spirit in power and grace is a discipline I would encourage all Emergent thinkers to investigate without prejudice.

Even as I write this, it is now possible to go online and find a

thing never before seen by religious people:

Mennonite Icons designed by Orthodox iconographers. The ancient icon makers and the iconoclasts have met, and are working together.

Can the Emergent conversation become a place where both worlds meet, dialogue, and learn to worship and celebrate together?

eggplantraisinsmokedgrapebasil.jpg) My son Elijah is having a kidney transplant in six days. People say things like, "That's great!" and then ask, "Are you excited?"

My son Elijah is having a kidney transplant in six days. People say things like, "That's great!" and then ask, "Are you excited?"